As I’ve mentioned, it was the 50’s—more precisely, the 1950’s. The 1950’s were a decade of great “progress.” Progress is a term people often employ when they feel that, overall, things are getting better. For instance, over the course of the 1950’s, American households transitioned from a total reliance on the media of “print” and “radio” (which had been around for hundreds of years and nearly forty years, respectively) to a new and spectacular medium of communication known as “television.” In order to experience this new medium of communication, one had to commit one’s full attention to it, since it was a “full audiovisual experience.” Naturally, people thought this way of communicating was superior than the old ways of simply reading or looking at pictures or listening to the radio—why do just one when you could do all three at the same time?!

There was one man who noticed all of this “progress” and hatched a scheme to make a great deal of money using a)television and b)fear of a nuclear holocaust. His name was Skeeter Scheems—The Most Scheming Man in the World.

Scheems was a child of the Dust Bowl, the environmental disaster that literally swept America’s heartland in the 1930’s. On April 14th, 1935, at the age of nine, he was working far out in a Kansas cornfield when the storms of Black Sunday hit. The grit scarred his corneas so badly that he never saw again.

Because he could no longer work on the farm, his parents sent him off to the Kansas State School for the Blind, where he excelled, especially in history, psychology, and art. Either because he was an introvert or because he started at the school later than the rest, Scheems was never able to make friends with his classmates, so every day after class he would lock himself in his dorm room, plant himself in his chair, and listen to the evening radio dramas such as “The Shadow,” “The Whistler,” and “The Adventures of the Thin Man.” Even after he left the school in 1945, Scheems would religiously post himself by his treasured radio from the hours of 5:30 to 9:30, transported into worlds of drama and intrigue he could see only in his mind’s eye.

On same the day he graduated, Scheems started working in the call center of Kansas City’s most popular radio station, KUDL. Over the next decade, he earned a number of promotions until, by 1955, he had held nearly every position in the company. But the year 1955 (the same year that the Pentagon announced its plan to deploy intercontinental ballistic missiles) proved to be a fatal year for KUDL and many other radio stations and programs, for one very important reason: television.

Jobless and destitute, Skeeter Scheems’ heart broke with each passing of his favorite radio dramas. The tipping point of his psychosis finally arrived as the last words of the final episode of “The Whistler” faded into static on September 22, 1955. As a sign-off, the series ended the way each episode began: with the sound of footsteps, a person whistling, and the unforgettable lines: “I am the Whistler, and I know many things, for I walk by night. I know many strange tales, hidden in the hearts of men and women who have stepped into the shadows. Yes ... I know the nameless terrors of which they dare not speak.” That night, embittered beyond cure by a world that had rejected all he had loved, Scheems stepped into the shadows. He defenestrated his radio from his third-story apartment (killing a cat in the process) and started scheming.

Chapter 4, The Big Apple

His first schemes were simple pyramid schemes and matrix schemes that collapsed after a few months, but not before raising thousands of dollars and clouds of judicial ire which Scheems would escape by mere hours. He would then travel to the next city, come up with the next catchy title, such as “The National Exchange,” or “Investors Unlimited,” then prey upon hordes of ignorant and gullible citizens. Scheems merely portrayed himself as a wholesome, handicapped entrepreneur, and his schemes practically sold themselves.

As 1956 dragged on, Scheems made ever-increasing amounts of cash—but he began to tire of his itinerant routine. As the frigid Midwestern winter set in, limiting his activities, a grander, more ambitious scheme began to quilt itself together in his mind. In late February, 1957, he decided to act on it—so he packed his bag and caught the next bus for The Big Apple.

Chapter 5, The Source

This is the part of the story when I make you realize how and where the trajectories of the protagonists and antagonist intersect.

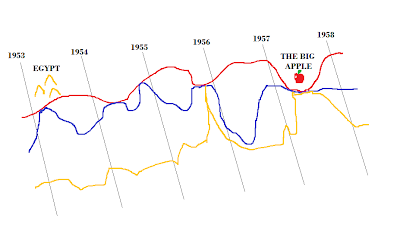

Legend: Red: The Relative Location of The Most Talented Man in the World. Blue: The Relative Location of The Most Interesting Man in the World. Yellow: The Relative Location of The Most Scheming Man in the World. So there you have it—the whole story lies in that picture. As you can see, the lives of The Most Interesting and Talented Men in the World had continued to intersect in the intervening four years, forging a lasting friendship. They both happened to be in The Big Apple for the spring and summer of 1957, the Most Talented Man in the World for the Fencing World Cup, various international summits, and high-profile development projects and The Most Interesting Man in the World for alleged buried treasure in downtown Manhattan (which he found) and for the planning stage of his next expedition to the Arctic. Scheems—soon to be the official Most Scheming Man in the World—arrived around the same time, and it wouldn’t be long before their paths crossed.

Parenthetically, you can also see that The Most Talented and Interesting Men in the World had almost met Skeeter Scheems in early 1955, when they gave a series of guest lectures at the University of Missouri- Kansas City School of Law just two blocks from KUDL. But I digress.

On a windy April morning in 1957, the Most Talented and Interesting Men in the World met up for coffee at a shop on Wall Street two hours before the Pulitzer Prize Ceremony, where The Most Interesting Man in the World would accept the prize for a book he had recently written entitled Me.

Here’s where it gets interesting.

Dispensing with formalities, The Most Interesting Man in the World steered the conversation toward an issue that had been troubling him that morning.

“Hey, have you heard of this new corporation called ‘Red Dawn Stock Options?’

“Never,” responded The Most Talented Man in the World.

“I just heard about it from a friend at the Stock Exchange yesterday—it’s very hush-hush. Anyway, the company offers exclusive stock options on other companies whose business would benefit in the case of nuclear war—hazardous waste disposal companies, companies like that I guess.”

The Most Talented Man in the World’s eyes narrowed. “‘Exclusive stock options.’ The only other time I’ve heard those words were in reference to Charles Ponzi, the famous swindler of the 1920’s.” After a brief pause, he continued, “I’d like to talk to this friend of yours down the Exchange. He available?”

“Now? Um, he should be.”

“Let’s pay him a visit. It’s just a couple blocks away.”

To summarize, the two extraordinary gentlemen found the trader, his source of information, his source’s source, and, after hours of sleuthing, his source’s source’s source. In the process, they forgot all about the Pulitzer Prize Ceremony-- which was ok since The Most Talented Man in the World planned on winning it the next year. But finding the first four levels of information on "Red Dawn Stock Options" was the easy part. The hard part came over the next three weeks, as they tracked the wispy traces of the trader’s source’s source’s source’s source: The Most Scheming Man in the World.

Stay tuned, beloved audience. You're not going to want to miss this showdown.

No comments:

Post a Comment